| Issue |

Ann. For. Sci.

Volume 67, Number 3, May 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 305 | |

| Number of page(s) | 11 | |

| Section | Original articles | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/forest/2009112 | |

| Published online | 18 February 2010 | |

Original article

Mortality of silver fir and Norway Spruce in the Western Alps – a semi-parametric approach combining size-dependent and growth-dependent mortality

Mortalité du sapin pectiné et de l’épicea commmun dans les alpes occidentales – une approche semi-paramétrique combinant la mortalité dépendant de la taille et de la croissance

1

Cemagref–Mountain Ecosystems Research Unit, 2 rue de la Papeterie, BP 76,

38402

Saint-Martin-d'Hères Cedex,

France

2

AgroParisTech–UMR1092, Laboratoire d'Étude des Ressources Forêt

Bois,

14 rue Girardet, 54000

Nancy, France

3

Cirad–UPR Dynamique Forestière, TA C-37/D, Campus International de

Baillarguet,

34398

Montpellier Cedex 5,

France

4

INRA–UMR1092, Laboratoire d'Étude des Ressources Forêt Bois,

14 rue Girardet, 54000

Nancy, France

5

ONF–Département Recherche, Boulevard de Constance,

77300

Fontainebleau,

France

* Corresponding author:

ghislain.vieilledent@cirad.fr

Received:

21

April

2009

Accepted:

4

September

2009

• Question: Tree mortality can be modeled using two complementary covariates, tree size and tree growth. Tree growth is an integrative measure of tree vitality while tree diameter is a good index of sensitivity to disturbances and can be considered as a proxy for tree age which may indicate senescence. Few mortality models integrate both covariates because classical model calibration requires large permanent plot data-sets which are rare. How then can we calibrate a multivariate mortality model including size and growth when permanent plots data are not available?

• Location: To answer this question, we studied Abies alba and Picea abies mortality in the French Swiss and Italian Alps.

• Method: Our study proposes an alternative semi-parametric method which includes a random sample of living and dead trees with diameter and growth measurements.

• Results: We were able to calibrate a mortality model combining both size-dependent and growth-dependent mortality. We demonstrated that A. alba had a lower annual mortality rate (10%) than P. abies (18%) for low growth (< 0.2 mm year−1). We also demonstrated that for higher diameters (DBH ≥ 70 cm), P. abies had a higher mortality rate (0.45%) than A. alba (0.32%).

• Conclusion: Our results are consistent with the mechanisms of colonization-competition trade-off and of successional niche theory which may explain the coexistence of these two species in the Alps. The method we developed should be useful for forecasting tree mortality and can improve the efficiency of forest dynamics models.

Résumé

• Question: Il est possible de modéliser la mortalité des arbres en utilisant deux covariables complémentaires : la taille et la croissance de l’arbre. La croissance est une mesure synthétique de la vitalité alors que le diamètre est un bon indicateur de la sensibilité aux perturbations et est très fortement corrélé à l’âge de l’arbre, qui détermine la sénescence. Peu de modèles de mortalité intègrent les deux covariables, car cela nécessite, pour les approches classiques, une calibration à partir de données de placettes permanentes qui sont rares. Comment obtenir un modèle de mortalité multivarié, incluant la taille et la croissance, lorsque des données de placettes permanentes ne sont pas disponibles ?

• Localisation géographique: Pour répondre à cette question, nous avons étudié la mortalité du sapin pectiné (Abies alba) et de l’epicéa commmun (Picea abies) dans les Alpes suisses françaises et italiennes.

• Méthode: Notre étude propose une méthode semi-parametrique alternative s’appuyant sur un échantillon d’arbres morts et vivants avec des mesures de diamètre et de croissance.

• Résultats: Nous avons obtenu un modèle combinant la mortalité dépendant à la fois de la taille et de la croissance. Nous avons démontré qu’A. alba avait un taux de mortalité inférieur (10 %) à celui de P. abies (18 %) pour une faible croissance (< 0.2 mm an−1). De plus, pour de larges diamètres (DBH ≥ 70 cm), P. abies a un taux de mortalité supérieur (0.45 %) à A. alba (0.32 %).

• Conclusion: Nos résultats sont en accord avec les mécanismes de niche de succession et de compromis entre colonisation et compétition qui sont invoqués pour expliquer la coexistence des deux espéces dans les Alpes. Notre méthode devrait contribuer à améliorer la prédiction du taux de mortalité et la précision des modèles de dynamique forestière.

Key words: Abies alba / conditional probability / non-parametric model / Picea abies / tree mortality

Mots clés : Abies alba / probabilités conditionnelles / modèles non-paramétriques / Picea abies / mortalité des arbres

© INRA, EDP Sciences, 2010

Abbreviations: DBH: Diameter at Breast Height (DBH = 1.30 m), P. abies: Picea abies (L.) Karst. (Norway Spruce), A. alba: Abies alba Mill. (Silver Fir), NFI: National Forest Inventory.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. The tree mortality process

Natural mortality of trees is an important mechanism driving forest dynamics (Monserud and Sterba, 1999). In forest dynamics models, the mortality provides a quantitative description of several species life-history traits, such as longevity or shade-tolerance, that determine species succession or coexistence (Harcombe, 1987).

Natural mortality of trees can be separated in two categories: regular and irregular mortality (Hawkes, 2000; Lee, 1971; Monserud, 1976). Regular mortality is associated with a progressive reduction in vitality. It can result either from competition for light, water and soil nutrients (Peet and Christensen, 1987) or from senescence defined as a decrease in resource utilization efficiency because of limitations in respiratory efficiency or hydraulic conductance (Gower et al., 1996; Hubbard et al., 1999; MacFarlane et al., 2002). Irregular mortality can be described as mortality caused by random events or hazards, e.g. by insect attacks, fire, wind, snow or rock falls (Lee, 1971) which are frequent in highly disturbed mountain stands (Clark, 1996; Coomes et al., 2003; Nishimura, 2006; Worrall et al., 2005). Decreasing vitality also leads to increasing susceptibility to fatal agents, e.g. insects, fungi and drought, so that irregular and regular mortality interact together to determine tree death.

From a statistical point of view, mortality can be modeled using two complementary covariates: tree size and tree growth. Growth is an integrative measure of tree vitality which, at a young age, depends principally on competition. For a given size, fast growing individuals are supposed to have a higher survivorship than slow growing individuals (Bigler and Bugmann 2003; Kobe and Coates 1997; Kunstler et al. 2005; Lin et al. 2001; Monserud 1976; Wyckoff and Clark 2000; 2002). In combination with growth, tree diameter is a good index of sensitivity to disturbances. Bigger trees with bigger crowns are more sensitive to hard wind and heavy snow whereas smaller trees are protected by the canopy (Canham et al., 2001; Fridman and Valinger, 1998; Peltola et al., 1999; Valinger and Fridman, 1997). Moreover it seems that insects affect preferentially older trees (Zolubas, 2003) and that fires and large mammals cause mortality among small trees (Muller-Landau et al., 2006). Tree diameter can also be considered as a proxy for tree age which determines the senescence.

1.2. Taking into account both size- and growth-dependent mortality in a flexible model

Despite its importance in determining species strategies and forest dynamics, tree mortality is difficult to model (Franklin et al., 1987; Hawkes, 2000). Most mortality models in forest systems predict only growth-dependent mortality for juveniles (Kobe et al., 1995; Kunstler et al., 2005) or a specific type of size-dependent irregular mortality (Hawkes, 2000; Monserud, 1976). In her review on woody plant mortality algorithms, Hawkes (2000) underlined that only a third of the models integrate combinations of covariates to determine mortality. Many of them combine competition indexes and size (Eid and Tuhus, 2001; Moore et al., 2004; Uriarte et al., 2004; Yao et al., 2001). Competition affects the carbon balance of a tree by depriving it of resources. Nevertheless, since competition, age and abiotic factors all affect growth, growth is a more integrative measure of whole-plant carbon balance, which determines tree vitality (Kobe et al., 1995). Tree growth can be estimated from tree-ring series, which provide high resolution records of tree growth, or from consecutive permanent plot censuses which provide a coarser resolution of growth through DBH increment measures (Wunder et al., 2007). Permanent plot surveys are less destructive than tree coring, but they require at least three censuses on long time intervals to link mortality observations between the second and third census to past growth between the two first censuses. Such experimental devices are not always available (but see Wunder et al., 2007; and Monserud, 1976) so that some authors have proposed statistical methods to obtain mortality-growth models from a reduced sample of dead and living trees from a single census (Kobe et al., 1995; Wyckoff and Clark, 2000). Nevertheless, no methods are available that combine both growth and size in a multivariate mortality model when no permanent plot data are available.

When permanent plot data are available, competition indexes (or growth) and size are often combined in a parametric regression, such as the logistic regression, to determine mortality estimates (Eid and Tuhus, 2001; Fortin et al., 2008; Moore et al., 2004; Uriarte et al., 2004; Wunder et al., 2007; Yao et al., 2001). Parametric functions have two disadvantages when trying to calibrate mortality models. First, they assume a strict model shape which may not conveniently represent the highly skewed shape of mortality given growth and size. Second, their estimations depend on the distribution of the data points which are often unbalanced in regard to diameter with less observations for big trees (Lavine, 1991; Vieilledent et al., 2009; Wyckoff and Clark, 2000).

Cemagref permanent plot characteristics.

1.3. Objectives and hypothesis

In this study we propose an alternative semi-parametric method using conditional probabilities to model both size-dependent and growth-dependent mortality using diameter and past radial growth as covariates. The method is applicable when no long-term permanent plot data are available. The approach relies principally on a prior mortality rate that can be obtained from National Forest Inventories. The prior is combined with diameter and growth data obtained for a sample of living and dead trees on a reduced number of plots.

We focused on two species: Abies alba Mill. (Silver Fir) and Picea abies (L.) Karst. (Norway Spruce), which grow in mixed or pure stands at the mountain-belt elevation (800–1800 m) in the Western Alps. Our objective was to accurately model size- and growth-dependent mortality for these two species providing insights into species strategies and dynamics. Our ecological hypothesis were (i) A. alba survives better at low growth rates than P. abies as it is more shade-tolerant and (ii) P. abies is more susceptible to mortality than A. alba for larger diameters because it is more sensitive to drought, insects, snow damage and storms at this elevation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Field data for mortality-diameter model

Mortality modelling was based on three different data-sets: (i) Swiss national forest inventory (NFI), (ii) French NFI, and (iii) permanent-plots from the Cemagref network.

The Swiss NFI includes 1982 permanent sample plots established between 1983 and 1985 and measured again between 1993 and 1995. Tree attributes (tree species, status dead or alive and DBH) were collected on two concentric circular plots, 200 m2 for trees of at least 12 cm DBH and 500 m2 for trees of at least 36 cm DBH (Ulmer, 2006). Logged trees were not taken into account. The Swiss NFI stands were dominated by A. alba or P. abies and had an elevation from 800 to 1800 m (mountain-belt elevation). Plots were all situated in the Swiss Alps.

The French NFI was analyzed for the twelve administrative areas that constitute the French Alps. Measurements are available from 1992 to 2002 on 4776 temporary plots and are part of the third NFI. Tree attributes were measured on three concentric circular plots with a radius of 6, 9 and 15 m for trees having DBH between 7.5 and 22.5 cm, between 22.5 and 37.5 cm and above to 37.5 cm, respectively. Dead trees for which death was estimated to be less than 5 y were identified on the basis of the dates of past tempests and the state of the bark. Similar to the Swiss NFI, logged trees were not included in the analysis.

The two NFIs were complemented by 7 permanents-plots from the Cemagref network located in the French Alps. Plots were installed from 1994 to 2002 and were measured again from 2005 to 2006 (Tab. I). No silvicultural operations had been performed on these plots for at least ten years before installation. Plots ranged from 0.25 to 0.80 ha. Stands were dominated by A. alba and P. abies. Plot elevations ranged from 800 to 1800 m. All trees with a minimum of 5 cm DBH were measured.

Combining these three data-sets, a large sample size was available for analysis with a total of 22127 A. alba and 45237 P. abies.

2.2. Mortality-diameter model

We used a semi-parametric Bayesian approach to estimate the mortality-diameter model parameters. This approach relied on a modified Ayer’s algorithm fully detailed in a previous article (Vieilledent et al., 2009). The semi-parametric model divided the range of diameters into bins and then calculated the associated probabilities of mortality. The model assumed a monotonic decrease of mortality on the interval [0,D0) followed by a monotonic increase of mortality on the DBH interval [D0,135) (DBH in cm). D0 was the diameter at which the mortality was minimal. The modified Ayer’s algorithmallowed us to identify D0 (D0 = 45cm for both species) and the sequence of diameter bins which respects our assumption of decreasing and increasing mortality with DBH.

For each identified DBH class, we estimated an annual mortality rate using a Bayesian

approach. Let zij be the event that

individual i of diameter class j survived

(zij = 1) or died

(zij = 0) during a time interval

Yi (in years) with probability 1 −

μ′Dij,

zij ∼

Bernoulli(zij | 1 −

μ′Dij). We

expressed 1 − μ′Dij as a

function of the annual mortality rate

μDj

associated with diameter class j and

Yi:  (1)We used a logit transformation for mortality rate:

(1)We used a logit transformation for mortality rate:

(2)Priors for the parameters

λDj were

taken non-informative with a large variance:

λDj ∼

Normal(0,1.0 × 106). We obtained a posterior distribution

for each parameter from which we computed the mean, the standard deviation, and the 95%

quantiles.

(2)Priors for the parameters

λDj were

taken non-informative with a large variance:

λDj ∼

Normal(0,1.0 × 106). We obtained a posterior distribution

for each parameter from which we computed the mean, the standard deviation, and the 95%

quantiles.

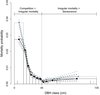

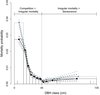

2.3. Field data including growth and diameter for dead and living trees

Growth data for dead and living trees were not available in the NFI data-sets. To estimate size and recent growth history for dead and living trees, we measured the DBH and we cored all recently dead trees and a random sample of living trees with height > 1.30 m on the 7 Cemagref plots. We completed the data-set for living trees adding two more plots which were located in the Italian Alps (Tab. I). The annual mean radial growth on the last five years was obtained from analysis of cores using the LINTAB 5 measuring table and the TSAP software. We measured the DBH of all dead and sampled living trees using a metric diameter tape. A total of 520 living trees and 53 dead trees were measured for A. alba and 458 and 179 for P. abies. For living trees, using core analysis on a time interval of 25 y, we obtained several values of DBH and past radial growth. A total of 2589 measurements for living trees and 53 mesurements for dead trees were obtained for A. alba and 2270 and 179 for P. abies (Fig. 1).

As we had no idea of the date of death of dead trees and as we only cored a sample of living trees on each plot, we lacked the proportions of living and dead trees to determine an annual mortality rate (Wyckoff and Clark, 2000). In this case, classical statistics such as logistic regressions (Monserud and Sterba, 1999; Wunder et al., 2007) cannot be used to estimate annual mortality rate as a function of past radial growth and diameter. Nevertheless, it is possible to compute the probability for a dead tree to be in the diameter (D) class j and in the growth (G) class k: p(Dj,Gk | dead) and the corresponding probability for a living tree: p(Dj,Gk | alive). Taken together, these two probabilities can be used to compute the annual mortality rate given diameter class j and growth class k: p(dead | Dj,Gk) (see next part for details).

Too few dead trees were measured for large diameters (DBH ≥ D0) with 3 and 4 dead trees with DBH ≥ 45 cm for A. alba and P. abies respectively (Fig. 1). As a consequence, we were not able to accurately decompose annual mortality rate for diameter and growth classes for this diameter range. For trees with DBH ≥ D0 we only obtained mortality rate estimates as a function of diameter using National Forest Inventories and Cemagref permanent plot data. This should not affect the quality of the mortality model for larger trees. Indeed, competition, which affects growth, occurs principally for small trees. Moreover, senescence, which is assumed to affect the growth of all trees of the same age in the same way, is taken into account through the diameter covariate, which can be considered as a proxy for age.

|

Figure 1 Data repartition for dead and living trees in regard to growth and diameter. A total of 2589 living trees (grey unfilled dots) and 53 dead trees (black filled dots) were measured for A. alba and respectively 2270 (grey cross) and 179 (black filled triangle) for P. abies. Too few dead trees were measured for large DBH (see respectively 3 and 4 dead trees for A. alba and P. abies with DBH ≥ 45 cm) to have the ability to decompose mortality given growth and diameter on this range of diameter. We used a local smoother (see function lowess() in R 2.5.0, Ihaka and Gentleman, 1996) to visualize growth-diameter relationship for dead (black curves) and living trees (grey curves) for A. alba (plain lines) and P. abies (dashed lines). The smoother indicated that past radial growth was lower for dead trees than for living trees for both species, whatever the diameter value. |

2.4. Mortality rate integrating both DBH and past radial growth for each species

2.4.1. Use of the Bayes formula to compute the combined mortality rate

For smaller trees (with DBH < D0), we obtained the

combined mortality rate

μDGjk

= p(deadD <

D0 |

Dj,Gk)

as a function of the diameter class j and the growth class

k using the Bayes’ formula and the prior probability of death for a

tree with DBH < D0 that we denoted

μD <

D0 = p(deadD

< D0):  (3)We denoted

Rjk the following ratio of probabilities:

(3)We denoted

Rjk the following ratio of probabilities:

(4)The two terms of the ratio were expressed as functions

of

dDGjk

and

nDGjk

−

dDGjk,

the number of dead and living trees in diameter class j and growth

class k respectively (Eqs. (5) and

(6)). This led to simple expressions for the ratio of

probabilities Rjk (Eq. (7)) and for the combined mortality rate

μDGjk

(Eq. (8))

(4)The two terms of the ratio were expressed as functions

of

dDGjk

and

nDGjk

−

dDGjk,

the number of dead and living trees in diameter class j and growth

class k respectively (Eqs. (5) and

(6)). This led to simple expressions for the ratio of

probabilities Rjk (Eq. (7)) and for the combined mortality rate

μDGjk

(Eq. (8))  (5)

(5) (6)

(6) (7)

(7) (8)

(8)

2.4.2. Determination of the prior

To compute

μDGjk

we needed to determine μD <

D0 =

p(deadD <

D0), which is the prior probability of death for a

tree with DBH < D0 (Eq. (8)). We selected the trees with DBH < D0

in the NFI data-sets and in the Cemagref permanent plots which integrated diameter

measures. We estimated μD <

D0 using a Bayesian approach. Let

yi be the event that individual

i with DBH < D0 survives

(yi = 1) or dies

(yi = 0) during a time interval

Yi (in years) with probability 1 −

μ′D <

D0, yi

∼ Bernoulli(yi | 1 −

μ′D <

D0). We expressed 1 −

μ′D <

D0 in function of the annual mortality rate

μD <

D0:  (9)We used a logit transformation for mortality rate:

(9)We used a logit transformation for mortality rate:

(10)and the prior for parameter

λD <

D0 was taken non-informative with a large variance:

λD <

D0 ∼

Normal(λD <

D0 | 0,1.0 × 106). We

then obtained a posterior distribution for parameter

μD <

D0 for each species from which we computed the mean,

the standard deviation, and the 95% quantiles.

(10)and the prior for parameter

λD <

D0 was taken non-informative with a large variance:

λD <

D0 ∼

Normal(λD <

D0 | 0,1.0 × 106). We

then obtained a posterior distribution for parameter

μD <

D0 for each species from which we computed the mean,

the standard deviation, and the 95% quantiles.

2.4.3. Two-dimensional Ayer’s algorithm to determine diameter and growth bins

The mortality model given diameter and growth assumed that mortality rate was decreasing on [0,D0) for diameter (cm) and on [0,8) for growth (mm year−1). We then used a modified two-dimensional Ayer’s algorithm to determine diameter and growth bins that respected these two assumptions (Ayer et al., 1955; Vieilledent et al., 2009). Our algorithm began with arbitrarily small bin widths of 5 cm for diameter and of 0.1 mm year−1 for growth. Diameter of all living and dead trees was partitioned into bins j = 1,2,...,qD and growth was partitioned into bins k = 1,2,...,rG. A corresponding annual mortality rate for each bin μDGjk was estimated with equation (8). For each couple (j,k), we checked firstly that μDGjk > μDGj + 1,k and secondly that μDGjk > μDGj,k + 1. If the first inequality considering DBH was not respected, bins were expanded in regard to DBH: binjk ↤ binjk + binj + 1,k and data were re-binned: dDGjk ↤ dDGjk + dDGj + 1,k and nDGjk ↤ nDGjk + nDGj + 1,k. If the first inequality was respected but the second considering growth was not, bins were expanded in regard to growth: binjk ↤ binjk + binj,k + 1 and data were re-binned: dDGjk ↤ dDGjk + dDGj,k + 1 and nDGjk ↤ nDGjk + nDGj,k + 1. Each time a bin was modified, the algorithm restarted from j = 1 and k = 1. The process was continued until a monotonic decreasing sequence was reached on [0,D0) for diameter and on [0,8) for growth.

The initial number of bins mDG,Start was equal to qD,Start × rG,Start = 135 / 5 × 8 / 0.1 = 2160. When monotonicity was achieved with a decrease of mortality on [0,D0) for DBH (cm) and a decrease on [0,8) for growth (mm year−1), the final number of bins mDG,Final could be between 1 (one mean mortality rate for all trees with 0 ≤ DBH < D0 and 0 ≤ growth < 8) and mDG,Start. Final bin width was also variable, going from 5 to D0 for DBH width and from 0.1 to 8 for growth width. Contrary to classical parametric logistic approaches (Monserud, 1976; Wunder et al., 2007), the semi-parametric model structure we developed was not entirely specified a priori but was instead determined from data and the number of parameters were flexible and not fixed in advance.

2.5. Mortality-growth model

We were interested in comparing species behavior regarding growth-dependent mortality for

insights into species strategies and successional dynamics. For each class of growth

g of width equal to 0.2 mm year−1, we computed the annual

mortality rate

μGg:

(11)

(11)

|

Figure 2 Mortality-diameter semi-parametric model for A. alba and P. abies. Models for A. alba (black lines and dots) and P. abies (grey lines and triangles) are represented with posterior mean (—) and 95% quantiles (- - -). Bar widths represent bins values obtained from modified Ayer’s algorithm and bar height represent maximum likelihood estimates obtained within Ayer’s algorithm. Vertical lines on the DBH axis indicate range of data for A. alba (black) and P. abies (grey). |

3. RESULTS

3.1. Mortality-diameter relationship

Using NFI data and Cemagref plots, we were able to obtain a mortality-diameter model. For both species, we observed a U-shape mortality-DBH relationship with a minimum mortality rate D0 equal to 45 cm (Fig. 2). For the smallest diameter class (DBH < 15 cm), P. abies had a higher mortality rate (3.76%) than A. alba (2.75%). For high diameters (DBH ≥ 45 cm), P. abies had a higher mortality rate than A. alba (Fig. 2) with a maximum mortality rate of 0.45% for P. abies and 0.32% for A. alba in the biggest DBH class (Tab. II).

To compute the combined size-dependent and growth-dependent mortality, we needed to estimate a prior mortality probability for DBH < 45 cm. On this diameter range, P. abies had a significantly higher annual mortality rate prior (1.49%) than A. alba (1.38%) (Fig. 3).

3.2. Mortality-growth relationship

For both species, mortality rate was increasing as growth was decreasing (Fig. 4). Fast growing individuals ( > 0.6 mm year−1) had a lower annual mortality rate ( < 2%) than slow growing individuals (Tab. II and Fig. 4).

For the same value of growth, P. abies had a higher mortality rate than A. alba (Tab. II and Fig. 4). The difference of mortality rate between the two species was increasing as growth was decreasing with a mortality rate for growth inferior to 0.2 mm year−1 of 18.42% for P. abies against 10.21% for A. alba (Tab. II). We demonstrated that, in our context, A. alba survived better at low growth rates than P. abies.

3.3. Size- and growth-dependent mortality model

The semi-parametric model allowed a flexible description of mortality as a function of diameter and growth for DBH < 45 cm. With our method, we were able to differentiate growth-related and size-related mortality on that range of diameter (Fig. 5). For a given DBH class, a less vigorous tree with a lower growth had a higher mortality rate than a more vigorous tree with a higher growth (Fig. 5). The semi-parametric model didn’t assume a strict model shape and allowed us to represent the skewed shape of the mortality surface (Fig. 5).

The low number of data for large trees (DBH ≥ 45 cm) (Fig. 1) didn’t permit a separation of growth-related mortality from size-related mortality. Because growth-related mortality affects principally small sub-canopy trees susceptible to competition, this should not affect the quality of the mortality model for large trees. For large trees (DBH ≥ 45 cm), size-related mortality referred both to irregular mortality and senescence (Figs. 2 and 5).

Values of annual mortality rate given diameter or growth. The annual mortality probability associated to diameter class j is μDj and the annual mortality rate given growth class g is μGg. For diameter class j, nDj is the total number of trees and dDj is the number of dead trees. For growth class g, nGg is the total number of trees and dGg is the number of dead trees.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. A model combining size-dependent and growth-dependent mortality

The mortality model we developed integrates both size-dependent and growth-dependent mortality which are taken into account through diameter and past radial growth covariates. Tree mortality increased with decreasing growth for smaller trees (DBH < 45 cm) affected by competition. Mortality had a U-shape relation with diameter accounting for disturbance-related mortality and senescence.

Most mortality models published to date have focused on one type of mortality. Some authors studied only carbon balance related mortality using growth as covariate (Bigler and Bugmann, 2003; Dobbertin, 2005; Kobe and Coates, 1997; Kunstler et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2001; Monserud, 1976; Wyckoff and Clark, 2000; Wyckoff and Clark, 2002). A limitation of this approach is that growth-mortality models alone are not sufficient for a good description of mortality as disturbances are not taken into account in the mortality process. Secondly, in forest dynamics models, tree growth is often related to local resource availability such as quantity of light (Courbaud et al., 2003), soil moisture or quantity of nutrients (Korzukhin and Ter-Mikaelian, 1995; Lexer and Hönninger, 2001). But, resource availability may not be the limiting factor for growth and carbon balance. For older trees, senescence mechanisms such as decreasing respiratory efficiency and decreasing hydraulic conductance may limit growth. Such mechanisms are not easily quantified and implemented in forest dynamics models. Adding a mortality-diameter relation with an increasing mortality for DBH ≥ 45 cm allows taking into account mortality associated with senescence mechanisms. Other authors studied mortality due only to specific disturbances such as rock fall, insects (Hansen et al., 2006), snow damage (Fridman and Valinger, 1998; Peltola et al., 1999) or windthrows (Canham et al., 2001) without considering growth-related mortality so that a tree with high growth and a tree with low growth were not differentiated in terms of mortality probability.

Some other models integrated both types of mortality. In the 1996 version of SORTIE model (Pacala et al., 1996), regular mortality was growth-dependent and was combined to a fixed background mortality rate of 1% assigned to both juvenile and adult trees. Depending on the model version, irregular mortality associated with severe disturbances such as windthrow was added (Papaik and Canham, 2006). In the ForClim model (Bugmann, 1994), mortality was divided into age-related mortality, stress-induced mortality and disturbance-related mortality. In these cases, mortality models did not use specifically collected data, but empirical data collected in other locations or sensible estimates (Hawkes, 2000). In contrast, our method allows an estimation of mortality rate combining both size-dependent and growth-dependent mortality from field observations. It should be mentioned that site environmental factors (such as topography, altitude, soil or climate) may modulate the relationship between size, growth and mortality (Das et al., 2008). The model described in this study only reflects average site conditions but not local site conditions.

|

Figure 3 Small trees mortality prior (μD < D0) for A. alba and P. abies. Prior probability distributions for A. alba (bold plain line) and P. abies (thin plain line) are compared. Vertical plain line indicates the mean and vertical dashed lines indicate 95% credible interval. For trees with DBH < 45 cm, P. abies has an annual mortality rate significantly higher than A. alba. |

|

Figure 4 Mortality-growth semi-parametric model for small trees (DBH < D0) of A. alba and P. abies. Mortality estimates μGg for each growth class g of range 0.2 mm year−1 were obtained integrating the combined mortality rates μDGjk on all diameter classes j and growth class intersections k ∩ g (see Eq. (11)). Mean posterior for A. alba (black lines and dots) and P. abies (grey lines and triangles) are represented. Bar widths represent fixed bins values of 0.2 mm year−1 for growth and bar height also represent the mean posterior. 95% credible intervals due to uncertainty on priors were too narrow to be represented on the graph. From this graph, we can see that for small trees (DBH < 45 cm) at low growth (growth < 0.6 mm year−1), P. abies has a higher mortality rate than A. alba. |

4.2. A flexible model making the most of available data

The semi-parametric approach we developed allowed us to obtain a flexible representation of the two-dimensional and highly skewed shape of mortality given growth and diameter. Other authors have developed parametric regressions (such as logistic regression) using permanent plot data which included both growth (either directly or indirectly through competition indexes) and size to obtain synthetic mortality models including regular and irregular mortality (Eid and Tuhus, 2001; Fortin et al., 2008; Moore et al., 2004; Uriarte et al., 2004; Wunder et al., 2007; Yao et al., 2001). Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that due to unbalanced data-sets from permanent plots and to the highly skewed shape of mortality, parametric models assuming a strict model shape may lead to biased mortality estimates and wrong interpretations concerning species life-history traits differences (Lavine, 1991; Vieilledent et al., 2009; Wyckoff and Clark, 2000). The semi-parametric model we developed didn’t assume a strict model shape and is less dependent on the distribution of the data points.

In order to parameterize classical logistic regressions for mortality estimation, one requires large data-sets based on permanent plot survey with multiple censuses over long time periods (Hawkes, 2000; Wunder et al., 2007). To account for growth, at least three censuses are needed to link mortality observation between the second and third census to growth between the two first censuses. Monserud 1976 used data obtained from 20–28 y of observations and Wunder et al. (2007 used a permanent plot network initiated in the late 1940’s. Such experimental devices with long-term data are rare. Some authors have previously described methods using a reduced sample of dead and living trees with growth measurements to avoid the use of permanent plot data for growth-related mortality (Kobe et al., 1995; Wyckoff and Clark, 2000). We extended the method to a multivariate mortality model including both size and growth. As the mortality prior can be obtained from bibliography or previous studies, the only data needed is a random sample of dead and living trees with DBH and past radial growth measures which can be used to obtain the inverse probabilities and the ratio of probabilities detailed in Equations (3) and (4). The method we propose is then simple and quick to implement when no permanent plot data are available.

4.3. A model which helps to understand and forecast A. alba and P. abies dynamics

With our model, we were able to demonstrate that A. alba was more resistant to low growth (< 0.6 mm year−1) than P. abies and that P. abies had a higher mortality rate than A. alba for high diameter (DBH ≥ 45 cm). As small trees are those receiving lower levels of light and having a lower growth, the better resistance of A. alba to low growth can be associated with its relative shade-tolerance compared to P. abies. These results match the classical accepted dynamics of mixed P. abies and A. alba stands which considers P. abies as being the relative early-successional species (Schüetz, 1969; Wasser and Frehner 1996). Early-successional plant species are supposed to have higher fecundity, longer dispersal, faster growth when resources are abundant, and slower growth and lower survivorship when resources are scarce compared to late-successional species (Rees et al., 2001). Such traits contribute to the competition-colonization trade-off (Tilman, 1994) and to the successional niche mechanisms (Pacala and Rees, 1998; Rees et al., 2001) which are commonly pointed up to explain species coexistence.

|

Figure 5 Multivariate mortality rate estimates for A. alba (a) and P. abies (b). Bins for diameter-classes and growth-classes were obtained with the modified two-dimensional Ayer’s algorithm. Mortality model is independent of growth for DBH ≥ 45 cm with the only assumption that mortality increases with diameter. For DBH < 45 cm, the model assumes that mortality decreases both with growth and diameter. Mortality model combines size-dependent and growth-dependent mortality. |

With regard to successional niche, previous studies have shown that P. abies saplings had higher growth at full light than A. alba (Grassi and Bagnaresi, 2001). Our results suggest that this advantage may be compensated by a higher mortality rate at low light for P. abies than for A. alba. With regard to colonization-competition trade-off, P. abies is supposed to have a higher fecundity and longer dispersal than A. alba (Dovčiak et al., 2008; Sagnard et al., 2007). This colonization advantage may be balanced by a lower competitive ability for P. abies than for A. alba when resources (typically light) are scarce (Schüetz, 1969; Wasser and Frehner, 1996). In regard to our results, we can argue that P. abies colonization advantage can also be compensated by a higher mortality rate for high diameter which can be interpreted as a lower life-span due to lower resistance to external perturbations such as rock-fall (Stokes et al., 2005), storms (Lundstrom et al., 2007) and insect attack (Zolubas, 2003) or to an earlier senescence.

To conclude, we emphasize the advantages of the mortality model we developed as (i) it includes both size-related and growth-related mortality (ii) making the most of the available mortality data (iii) without assuming a strict model shape for the mortality surface (iv) and allowing the accurate interpretion of species life-histories. Therefore, the method we propose should be of value in helping to understand and forecast forest community dynamics.

Acknowledgments

Grateful thanks are due to Marc Fuhr, Yoan Paillet, Eric Mermin and Pascal Tardif (the Cemagref) for field work, to Ulrich Ulmer (the WSL) and to the Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL for providing the Swiss National Forest Inventory data, to Renzo Motta (the University of Turin) for providing the Italian plot data, to Bernard Ycart (the Institute of Applied Mathematics of Grenoble) for mathematical help, and to Julian C. Fox (the University of Melbourne) for english editing. This work was supported by the Grenoble Cemagref, the French National Forest Office and by the French Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries.

References

- Ayer M., Brunk H.D., Ewing G.M., Reid W.T. and Silverman E., 1955. An empirical distribution function for sampling with incomplete information. Ann. Math. Stat. 26: 641–647 [Google Scholar]

- Bigler C. and Bugmann H., 2003. Growth-dependent tree mortality models based on tree-rings. Can. J. For. Res. 33: 210–221 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bugmann H., 1994. On the ecology of mountainous forests in a changing climate: a simulation study. Ph.D. thesis, Swiss federal institute of technology, Zürich. [Google Scholar]

- Canham C.D., Papaik M.J. and Latty E.F., 2001. Interspecific variation in susceptibility to windthrow as a function of tree size and storm severity for northern temperate tree species. Can. J. For. Res. 31: 1–10 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J.S., 1996. Testing disturbance theory with long-term data: Alternative life-history solutions to the distribution of events. Am. Nat. 148: 976–996 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coomes D.A., Duncan R.P., Allen R.B. and Truscott J., 2003. Disturbances prevent stem size-density distributions in natural forests from following scaling relationships. Ecol. Lett. 6: 980–989 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Courbaud B., de Coligny F. and Cordonnier T., 2003. Simulating radiation distribution in a heterogeneous Norway spruce forest on a slope. Agric. For. Meteorol. 116: 1–18 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Battles J., van Mantgem P.J. and Stephenson N.L., 2008. Spatial elements of mortality risk in old-growth forests. Ecology 89: 1744–1756 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbertin M., 2005. Tree growth as indicator of tree vitality and of tree reaction to environmental stress: a review. Eur. J. For. Res. 124: 319–333 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dovčiak M., Hrivnák R., Ujházy K. and Gömöry D., 2008. Seed rain and environmental controls on invasion of Picea abies into grassland. Plant Ecol. 194: 135–148 [Google Scholar]

- Eid T. and Tuhus E., 2001. Models for individual tree mortality in Norway. For. Ecol. Manag. 154: 69–84 [Google Scholar]

- Fortin M., Bedard S., DeBlois J. and Meunier S., 2008. Predicting individual tree mortality in northern hardwood stands under uneven-aged management in southern Quebec, canada. Ann. For. Sci. 65: 205. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin J.F., Shugart H.H. and Harmon M.E., 1987. Tree death as an ecological process. BioScience 550–556. [Google Scholar]

- Fridman J. and Valinger E., 1998. Modelling probability of snow and wind damage using tree, stand, and site characteristics from Pinus sylvestris sample plots. Scan. J. For. Res. 13: 348–356 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gower S.T., McMurtrie R.E. and Murty D., 1996. Aboveground net primary production decline with stand age: Potential causes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 11: 378–382 [Google Scholar]

- Grassi G. and Bagnaresi U., 2001. Foliar morphological and physiological plasticity in Picea abies and Abies alba saplings along a natural light gradient. Tree Physiol. 21: 959–967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen E.M., Bentz B.J., Munson A.S., Vandygriff J.C. and Turner D.L., 2006. Evaluation of funnel traps for estimating tree mortality and associated population phase of spruce beetle in Utah. Can. J. For. Res. 36: 2574–2584 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harcombe P.A., 1987. Tree life table. Bioscience 37: 557–568 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C., 2000. Woody plant mortality algorithms: description, problems and progress. Ecol. Model. 126: 225–248 [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard R.M., Bond B.J. and Ryan M.G., 1999. Evidence that hydraulic conductance limits photosynthesis in old Pinus ponderosa trees. Tree Physiol. 19: 165–172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihaka R. and Gentleman R., 1996. R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. J. Comp. Graph. Stat. 5: 299–314 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe R.K. and Coates K.D., 1997. Models of sapling mortality as a function of growth to characterize interspecific variation in shade tolerance of eight tree species of northwestern British Columbia. Can. J. For. Res. 27: 227–236 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe R.K., Pacala S.W. and Silander J.A., 1995. Juvenile tree survivorship as a component of shade tolerance. Ecol. Appl. 5: 517–532 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Korzukhin M.D. and Ter-Mikaelian M.T., 1995. An individual tree-based model of competition for light. Ecol. Model. 79: 221–229 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kunstler G., Curt T., Bouchaud M. and Lepart J., 2005. Growth, mortality, and morphological response of European beech and downy oak along a light gradient in sub-Mediterranean forest. Can. J. For. Res. 35: 1657–1668 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine M., 1991. Problems in Extrapolation Illustrated with Space-Shuttle O-Ring Data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 86: 919–921 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.J., 1971. Predicting mortality for even-aged stands of lodgepole pine. For. Chron. 47: 29–32 [Google Scholar]

- Lexer M.J. and Hönninger K., 2001. A modified 3D-patch model for spatially explicit simulation of vegetation composition in heteregeneous landscape. For. Ecol. Manage. 144: 43–65 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Harcombe P.A. and Fulton M.R., 2001. Characterizing shade tolerance by the relationship between mortality and growth in tree saplings in a southeastern Texas forest. Can. J. For. Res. 31: 345–349 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom T., Jonas T., Stockli V. and Ammann W., 2007. Anchorage of mature conifers: Resistive turning moment, root-soil plate geometry and root growth orientation. Tree Physiol. 27: 1217–1227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane D.W., Green E.J., Brunner A. and Burkhart H.E., 2002. Predicting survival and growth rates for individual loblolly pine trees from light capture estimates. Can. J. For. Res. 32: 1970–1983 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Monserud R.A., 1976. Simulation of forest tree mortality. For. Sci. 22: 438–444 [Google Scholar]

- Monserud R.A. and Sterba H., 1999. Modeling individual tree mortality for Austrian forest species. For. Ecol. Manage. 113: 109–123 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J.A., Hamilton D.A., Xiao Y. and Byrne J., 2004. Bedrock type significantly affects individual tree mortality for various conifers in the inland Northwest, USA. Can. J. For. Res. 34: 31–42 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Landau H.C., Condit R.S., Chave J., Thomas S.C., Bohlman S.A., Bunyavejchewin S., Davies S., Foster R., Gunatilleke S., Gunatilleke N., Harms K.E., Hart T., Hubbell S.P., Itoh A., Kassim A.R., LaFrankie J.V., Lee H.S., Losos E., Makana J.R., Ohkubo T., Sukumar R., Sun I.F., Supardi N.M.N., Tan S., Thompson J., Valencia R., Munoz G.V., Wills C., Yamakura T., Chuyong G., Dattaraja H.S., Esufali S., Hall P., Hernandez C., Kenfack D., Kiratiprayoon S., Suresh H.S., Thomas D., Vallejo M.I. and Ashton P., 2006. Testing metabolic ecology theory for allometric scaling of tree size, growth and mortality in tropical forests. Ecol. Lett. 9: 575–588 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T.B., 2006. Successional replacement mediated by frequency and severity of wind and snow disturbances in a Picea-Abies forest. J. Veg. Sci. 17: 57–64 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pacala S.W., Canham C., Saponara J., Silander J.A., Kobe R.K. and Ribbens E., 1996. Forest models defined by field measurements: estimation, error analysis and dynamics. Ecol. Monogr. 66: 1–43 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pacala S.W. and Rees M., 1998. Models suggesting field experiments to test two hypotheses explaining successional diversity. Am. Nat. 152: 729–737 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaik M.J. and Canham C.D., 2006. Species resistance and community response to wind disturbance regimes in northern temperate forests. J. Ecol. 94: 1011–1026 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peet R.K. and Christensen N.L., 1987. Competition and tree death. BioScience 37: 586–595 [Google Scholar]

- Peltola H., Kellomaki S., Vaisanen H. and Ikonen V.P., 1999. A mechanistic model for assessing the risk of wind and snow damage to single trees and stands of Scots pine, Norway spruce, and birch. Can. J. For. Res. 29: 647–661 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rees M., Condit R., Crawley M., Pacala S. and Tilman D., 2001. Long-term studies of vegetation dynamics. Science 293: 650–655 [Google Scholar]

- Sagnard F., Pichot C., Dreyfus P., Jordano P. and Fady B., 2007. Modelling seed dispersal to predict seedling recruitment: recolonization dynamics in a plantation forest. Ecol. Model. 203: 464–474 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schütz J.-P., 1969. Etude des phénomènes de la croissance en hauteur et en diamètre du sapin (Abies alba Mill.) et de l’épicéa (Picea abies Karst.) dans deux peuplements jardinés et une forêt vierge. Ph.D. thesis, École Polytechnique Fédérale Zurich, Zurich. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes A., Salin F., Kokutse A.D., Berthier S., Jeannin H., Mochan S., Dorren L., Kokutse N., Abd Ghani M. and Fourcaud T., 2005. Mechanical resistance of different tree species to rockfall in the French Alps. Plant Soil 278: 107–117 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D., 1994. Competition and biodiversity in spatially structured habitats. Ecology 75: 2–16 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer U., 2006. Schweizerisches Landesforstinventar LFI. Datenbank-auszug der Erhebungen 1983–85 und 1993–95 vom 30. Mai 2006. Technical report, WSL, Eidg. Forschungsanstalt WSL, Birmensdorf. [Google Scholar]

- Uriarte M., Canham C.D., Thompson J. and Zimmerman J.K., 2004. A neighborhood analysis of tree growth and survival in a hurricane-driven tropical forest. Ecol. Monogr. 74: 591–614 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Valinger E. and Fridman J., 1997. Modelling probability of snow and wind damage in Scots pine stands using tree characteristics. For. Ecol. Manage. 97: 215–222 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vieilledent G., Courbaud B., Kunstler G., Dhote J.F. and Clark J.S., 2009. Biases in the estimation of size-dependent mortality models: advantages of a semiparametric approach. Can. J. For. Res. 39: 1430–1443 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wasser B. and Frehner M., 1996. Soins minimaux pour les forêts à fonction protectrice. Office Central Fédéral des Imprimés et du Matériel, Berne. [Google Scholar]

- Worrall J.J., Lee T.D. and Harrington T.C., 2005. Forest dynamics and agents that initiate and expand canopy gaps in Picea-Abies forests of Crawford Notch, New Hampshire, USA. J. Ecol. 93: 178–190 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder J., Reineking B., Matter J.F., Bigler C. and Bugmann H., 2007. Predicting tree death for Fagus sylvatica and Abies alba using permanent plot data. J. Veg. Sci. 18: 525–534 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff P.H. and Clark J.S., 2000. Predicting tree mortality from diameter growth: a comparison of maximum likelihood and Bayesian approaches. Can. J. For. Res. 30: 156–167 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff P.H. and Clark J.S., 2002. The relationship between growth and mortality for seven co-occurring tree species in the southern Appalachian Mountains. J. Ecol. 90: 604–615 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X.H., Titus S.J. and MacDonald S.E., 2001. A generalized logistic model of individual tree mortality for aspen, white spruce, and lodgepole pine in Alberta mixedwood forests. Can. J. For. Res. 31: 283–291 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zolubas P., 2003. Spruce Bark Beetle (Ips typographus L.) Risk based on individual tree parameters. In: IUFRO (Ed.), Forest insect population dynamics and host influences, Kanazawa, pp. 96–97. [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Values of annual mortality rate given diameter or growth. The annual mortality probability associated to diameter class j is μDj and the annual mortality rate given growth class g is μGg. For diameter class j, nDj is the total number of trees and dDj is the number of dead trees. For growth class g, nGg is the total number of trees and dGg is the number of dead trees.

All Figures

|

Figure 1 Data repartition for dead and living trees in regard to growth and diameter. A total of 2589 living trees (grey unfilled dots) and 53 dead trees (black filled dots) were measured for A. alba and respectively 2270 (grey cross) and 179 (black filled triangle) for P. abies. Too few dead trees were measured for large DBH (see respectively 3 and 4 dead trees for A. alba and P. abies with DBH ≥ 45 cm) to have the ability to decompose mortality given growth and diameter on this range of diameter. We used a local smoother (see function lowess() in R 2.5.0, Ihaka and Gentleman, 1996) to visualize growth-diameter relationship for dead (black curves) and living trees (grey curves) for A. alba (plain lines) and P. abies (dashed lines). The smoother indicated that past radial growth was lower for dead trees than for living trees for both species, whatever the diameter value. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 2 Mortality-diameter semi-parametric model for A. alba and P. abies. Models for A. alba (black lines and dots) and P. abies (grey lines and triangles) are represented with posterior mean (—) and 95% quantiles (- - -). Bar widths represent bins values obtained from modified Ayer’s algorithm and bar height represent maximum likelihood estimates obtained within Ayer’s algorithm. Vertical lines on the DBH axis indicate range of data for A. alba (black) and P. abies (grey). |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 3 Small trees mortality prior (μD < D0) for A. alba and P. abies. Prior probability distributions for A. alba (bold plain line) and P. abies (thin plain line) are compared. Vertical plain line indicates the mean and vertical dashed lines indicate 95% credible interval. For trees with DBH < 45 cm, P. abies has an annual mortality rate significantly higher than A. alba. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 4 Mortality-growth semi-parametric model for small trees (DBH < D0) of A. alba and P. abies. Mortality estimates μGg for each growth class g of range 0.2 mm year−1 were obtained integrating the combined mortality rates μDGjk on all diameter classes j and growth class intersections k ∩ g (see Eq. (11)). Mean posterior for A. alba (black lines and dots) and P. abies (grey lines and triangles) are represented. Bar widths represent fixed bins values of 0.2 mm year−1 for growth and bar height also represent the mean posterior. 95% credible intervals due to uncertainty on priors were too narrow to be represented on the graph. From this graph, we can see that for small trees (DBH < 45 cm) at low growth (growth < 0.6 mm year−1), P. abies has a higher mortality rate than A. alba. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 5 Multivariate mortality rate estimates for A. alba (a) and P. abies (b). Bins for diameter-classes and growth-classes were obtained with the modified two-dimensional Ayer’s algorithm. Mortality model is independent of growth for DBH ≥ 45 cm with the only assumption that mortality increases with diameter. For DBH < 45 cm, the model assumes that mortality decreases both with growth and diameter. Mortality model combines size-dependent and growth-dependent mortality. |

| In the text | |